Engineers thrive in environments where they can focus and “get in the zone”. Teams often face many distractions and competing priorities that force engineers to shift context and divide their attention. They struggle to balance “heads down” time with “heads up” time. Adding new features requires team members to be heads down and focused. Responding to customer issues and addressing live site issues requires the team to be heads up and aware of what’s going on.

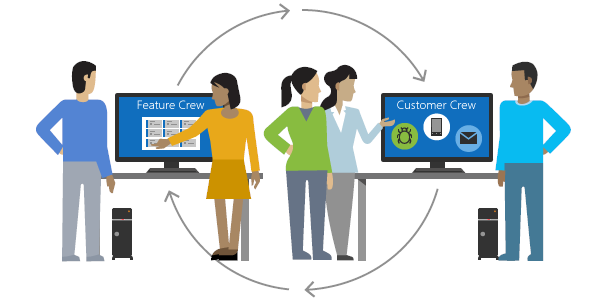

To mitigate distractions, a team can divide itself into two “crews”: one focused on feature work (design, code, review, test and documentation) and another focused on live site health (bug fixes, telemetry, live-site issues, and responding directly with customers).

The two-crew approach yields greater productivity and predictability. Successful implementation relies on these key elements:

- Clearly defined crew roles

- A well-defined crew rotation process

- Frequent adjustments to crew size

Feature crew

The feature crew (F-crew) focuses on the future. They work as an effective unit with a clear mission and goal: build and ship high quality features.

To ensure they have the time to design, build, and test their work, they are shielded from the day-to-day chaos of the live service. As part of the F-crew, they can rely on minimal distractions and freedom from having to fix issues that arise at random. They’re encouraged to seldom check their email and avoid getting pulled into other issues unless they’re absolutely critical.

When an F-crew member joins a conversation or occasionally gets sucked into an email thread, other team members should chide them: “You are on the F-crew, what are you doing?” If it is absolutely necessary for an F-crew member to address a critical issue, they are encouraged to delegate to the customer crew and return to feature work.

The F-crew operates as a tight-knit team that swarms on a small set of features. A good WIP limit is 2-features in flight for 4-6 people. By working closely together they build deep shared context and find critical bugs or design issues that a cursory code review would miss. This type of dedicated crew allows for a more predictable throughput rate and lead time. Team members often refer to the F-crew as serene and focused. They find it peaceful and rejuvenating to focus deeply on a feature, to dedicate full attention to it. People leave their time on the F-crew feeling refreshed and accomplished.

Customer crew

The customer crew (C-crew) focuses on the now, providing frontline support for customer and live-site issues, bugs, telemetry, and monitoring. The C-crew often huddles around a computer, debugging a critical live-site issue. Their number one priority is live-site health. Laser-focused on this environment, they build expert debugging and analysis skills. The customer crew is often referred to as the shield team, because it “shields” the rest of the team from distractions. Rather than working on upcoming features, the C-crew is the bridge between customers and the current product. They are active on email, twitter, and other feedback channels. Customers want to know they are heard, and the C-crew’s job is to hear them. The C-crew triages customer reported issues immediately and quickly engages and assists blocked customers.

With a deluge of incoming tasks, working on a fast-paced C-crew can, at times, be exhilarating. In a busy week, they address multiple emails, live-site investigations, and bugs. As operations quiet down, they work to improve telemetry and reporting, investing their time to make service upkeep easier.

C-crews allow the team to address issues without pulling team members off other priorities, and ensure customers and partners are heard. Responsiveness to questions and issues becomes a point of pride for C-crews. However, this pace can be draining, necessitating a frequent rotation between crews.

Crew rotation

A well-defined rotation process makes the two-crew system work. You could simply swap the crews (F-crew becomes C-crew and vice versa), but this limits knowledge sharing between and within the crews. Instead, opt for a weekly rotation.

At the end of each week conduct a short “Swap Meet”, where the team decides who swaps between crews. You can use a simple whiteboard chart to track who is currently on each crew and when they were swapped. The longest tenured people on each crew should typically swap with each other. However, in any given week, someone may want to remain to complete work on a live-site investigation or feature. While there is flexibility, the longer someone is on a crew, the more likely they should be swapped.

Weekly rotations help prevent silos of knowledge in the team and ensure a constant flow of information and perspective between crews. The frequent movement of engineers creates shared knowledge of the team’s work, which helps the C-crew to resolve issues without the help of others. Often times, new F-crew members will quickly find a previously overlooked design or code flaw.

Crew size

Crew size varies to maintain the health of the team. If a team has a high incoming rate of live-site issues or has a lot of technical debt, the C-crew gets larger, and vice versa. Adjusting sizes weekly increases predictability in the team’s deliverables and dependencies. Some weeks a team may move everyone to the C-crew to address the feedback from a big release.

This strategy simplifies communication with management. Without a two crew-system, engineers often work on multiple things simultaneously. When several distractions occur in a single week, in-progress features are often delayed. As a result, a team may be unable to confidently give timelines for future feature work.

A dedicated F-crew leads to predictable throughput and lead time. Splitting resources between crews increases accountability within the team and with management about what the team can accomplish each week and each sprint.

Final thoughts

The two-crew system can help teams struggling to understand where engineers should spend their time and to make progress on many competing priorities.

However, the two-crew system not only improves productivity and predictability, it increases team morale as well. Engineers on the team clearly understand their roles and responsibilities and function more independently and with much greater accountability. This approach is ideal for DevOps teams, those responsible for both development and operations. However, this approach can be applied to nearly any agile team dealing with competing priorities.

Try this approach on your team for a sprint or two. Use this article as the basis for your own approach, then learn from it and refine it to work for your team. Then, let us know how it works. You can find me on Twitter @mmanela.